During the 2024 presidential campaign, Trump stated, “On day one, I will launch the largest deportation program of criminals in the history of America.” “Operation at Large” targets unauthorized immigrants.

Racial injustice is linked to the geographic and environmental transformation of the U.S., and to the concept of place. Race, like ethnicity, is a cultural and social construct - terms that are irrevocably intertwined, reflecting multiple characteristics including language, culture, religion, and geography. Any discussion of race and ethnicity is fraught due to how these terms are defined and used interchangeably, yet they are part of the complex lexicon through which we understand place and identity.

Geographic flows can be expressed as patterns of movement where people are pushed, pulled, or taken from place - locales that hold meaning. Two groups dominate the historical geography of racial injustice in America: Native Americans and Africans. They represent two geographic flows of populations removed from their homelands—Native Americans were pushed, while Africans were taken. Other ethnic groups, such as Chinese, Japanese, Southeast Asians, Mexicans, and other Latin Americans, were pulled to place, arriving in the United States in search of economic opportunity, to flee political persecution, or to seek refuge. Underlying the arrival of these groups are powerful economic and political currents shaped by prejudice, fear, and violence.

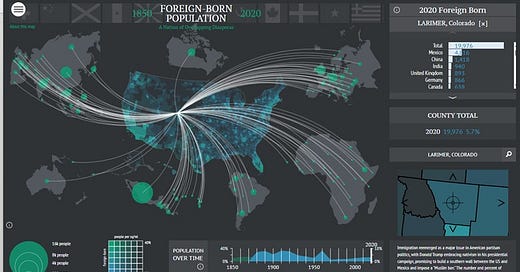

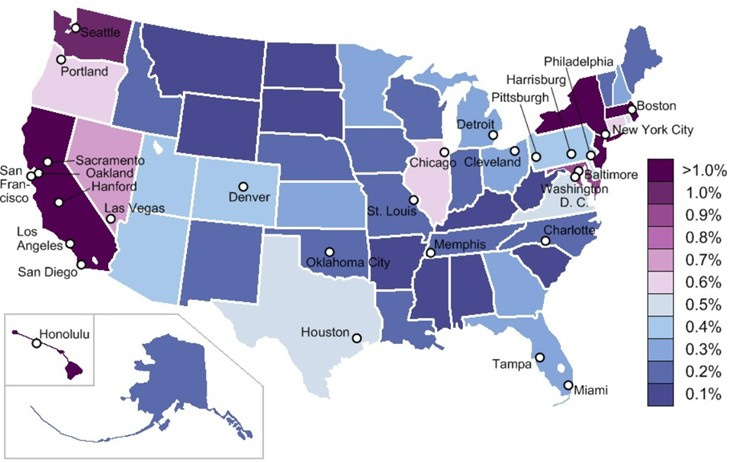

The United States is composed of immigrants, literally waves of people who arrived from the earliest days of conquest and settlement to the present. Immigrant groups form overlapping diasporas, contributing to a vibrant, multicultural society now under threat. Diaspora refers to the spread of people from their original geographic place. A significant portion of the U.S. population is foreign-born, influencing both culture and politics. The largest number of immigrants in the U.S. are from Mexico (10.6%), followed by India (6%), China (5%), the Philippines (4%), and El Salvador (3%).

Screenshot of Foreign-Born in Larimer County, CO from American Panorama’s Foreign-Born Population – A nation of Overlapping Diasporas (1850 – 2020), Digital Scholarship Lab, University of Richmond. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/foreignborn/#decade=2020&county=G0800690.

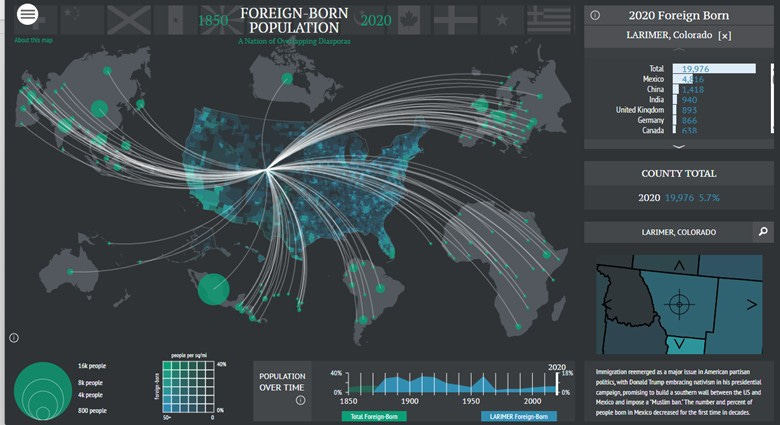

However, Native Americans are the First Peoples of the Western Hemisphere and were systematically displaced and dispossessed. Conflicting visions of place - communal aboriginal homelands versus individually owned property - were contested and ultimately overruled, as lands were consistently ceded to the United States

Map of Native American tribes. Sturtevant, William C, and U.S Geological Survey. National atlas. Indian tribes, cultures & languages: United States. Reston, Va.: Interior, Geological Survey, 1967. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/95682185/.

Legal tools such as treaties and laws were used to force tribes from their homelands, dismantle communities, and sequester populations onto ever-smaller units of land—reservations.

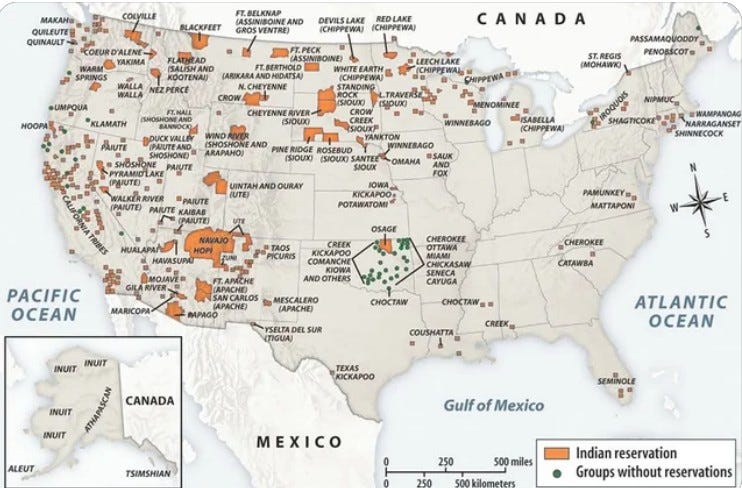

Native American reservations in the United States. https://www.reddit.com/r/MapPorn/comments/119fyy7/native_american_reservations_in_the_united_states/.

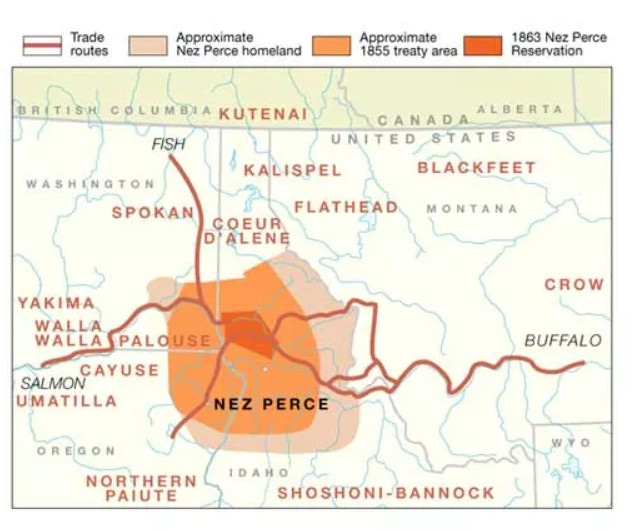

The U.S. signed multiple treaties with Indigenous peoples, breaking most, if not all, of them to enable the transformation of the western United States. One of the first treaties on the North American continent was between Ousamequin and English settlers in 1621. The first treaty signed by the U.S. Continental Congress was with the Lenape (Delaware) in 1778 - both intended for mutual protection from foreign powers such as the English. Over time, treaties reflected a growing power differential. For example, the 1855 Nez Perce Treaty was rewritten in 1863, reducing the reservation by 90% to allow gold-seeking miners into the region, leading to the 1877 U.S. military campaign against the Nez Perce.

Two laws specifically displaced Native Americans from their lands. The Homestead Act of 1862 opened the American West to settler colonialists - waves of immigrants - who could “occupy and improve” land and claim title after five years, often on Native lands classified as surplus. The General Mining Law of 1872 legitimized trespassing and prospecting on tribal lands, enabling mineral exploration and extraction. Many of these mines were later abandoned, leaving behind untreated mine waste that continues to contaminate headwater streams and groundwater near many reservations.

Treaty period 1855 – 1863. Source: NPS Photo. https://www.nps.gov/nepe/learn/historyculture/the-treaty-era.htm.

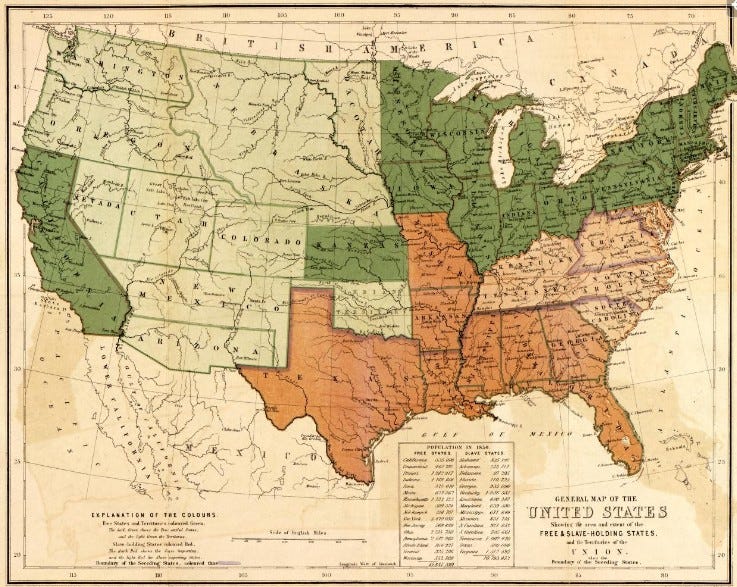

The legacy of slavery, from the arrival of the first slave ship in 1619 to the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, casts a long shadow over American geography. Africans were forcibly taken from their homelands to meet the economic demands of an emerging nation. Stolen lands were worked by stolen people; enslaved Africans grew cotton for the Atlantic market on land seized from Native Americans. One could add “stolen soil” to the list, as monocultures of tobacco and cotton exhausted soils, prompting expansion westward into Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas and the extension of slavery into new territories.

Map of United States Free & Slave Holding States. Dark green: Free settled states; Light green: Territories; Red: Slave-holding states (Dark red – Slave importing; Light red: Slave exporting). Rogers, Henry D, W. & A.K. Johnston Limited, and Edward Stanford Ltd. General map of the United States, showing the area and extent of the free & slave-holding states, and the territories of the Union: also the boundary of the seceding states. [London: E. Stanford ; Edinburgh: W. & A.K. Johnston, 1857] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/97682063/.

The legacy of slavery, from the arrival of the first slave ship in 1619 to the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, casts a long shadow over American geography. Africans were forcibly taken from their homelands to meet the economic demands of an emerging nation. Stolen lands were worked by stolen people; enslaved Africans grew cotton for the Atlantic market on land seized from Native Americans. One could add “stolen soil” to the list, as monocultures of tobacco and cotton exhausted soils, prompting expansion westward into Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas and the extension of slavery into new territories.

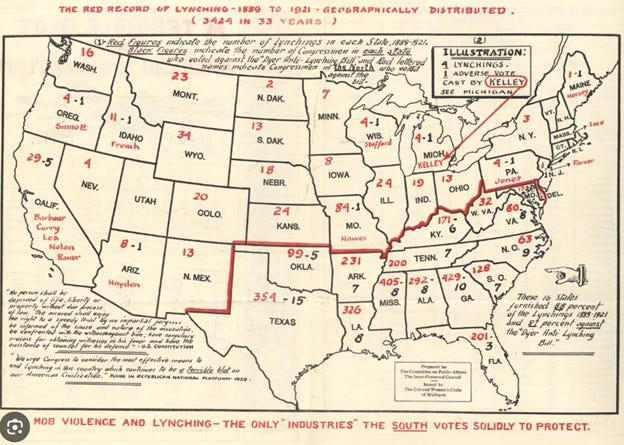

The Red Record of Lynching – 1889 – 1921, complied by Ida B. Wells. U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on the Judiciary, 1922. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/149268727

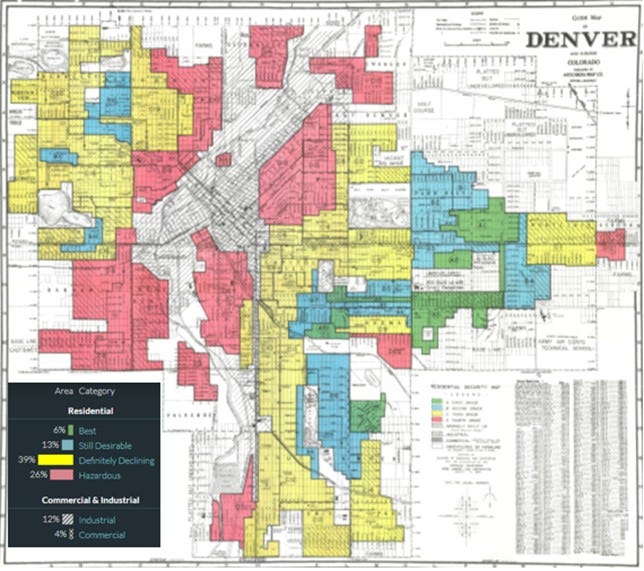

As African Americans redistributed into urban areas in the North and West, new forms of racial injustice emerged. Federal housing policies institutionalized redlining, which blocked Black households and communities of color from accessing mortgages and homeownership. Redlining and restrictive housing covenants were explicitly designed to exclude unwanted ethnic and racial groups.

Mapping inequality – Redlining in New Deal America (1935 – 1940. The U.S. Home Owner’s Loan Corporation graded residential security with amps as “best” (green) to “hazardous” (red). https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/map/CO/Denver/areas#loc=12/39.7104/-104.9693.

In the 1850s, Chinese workers migrated to California to mine gold, build the transcontinental railroad, and work in factories - pulled to the U.S. by opportunity and the desire to send remittances home. Many became business owners and farm operators. However, their economic success, often achieved through lower-wage contract work, generated hostility among white workers. Chinese communities, often clustered in ethnic enclaves or “Chinatowns,” were targeted in violent attacks and arson, including the Rock Springs Massacre, where 28 Chinese migrants were killed and 15 wounded.

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first law to place broad restrictions on immigration. It barred Chinese residents from obtaining U.S. citizenship and laid the groundwork for future immigration policy. The Immigration Act of 1924 established a national origins quota system based on the 1890 census and excluded immigrants from Asia. These laws institutionalized racial bias, establishing enduring systems of exclusion. The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act overturned the 1924 law, eliminating national origin quotas and racist barriers. Today, immigrants from China are the third-largest group in the U.S., and China is a top source of international students and highly skilled H-1B visa holders.

Percentage of Chinese population in the U. S. states (data source: 2000 Census); major Chinatowns in the U. S. Public domain: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chinese_Population_USA.jpg.

In the 1860s, Japanese immigrants came to Hawaii and the U.S. West Coast. The 1907 Gentlemen’s Agreement between the U.S. and Japan allowed the immigration of businessmen, students, and spouses of those already in the U.S., but Japanese immigration was effectively ended by the 1924 Immigration Act. Those already in the U.S. could not become citizens under the Naturalization Act of 1790, which restricted naturalization to "free white persons." As a result, they could neither vote nor own land. By World War II, most Japanese Americans were U.S.-born citizens.

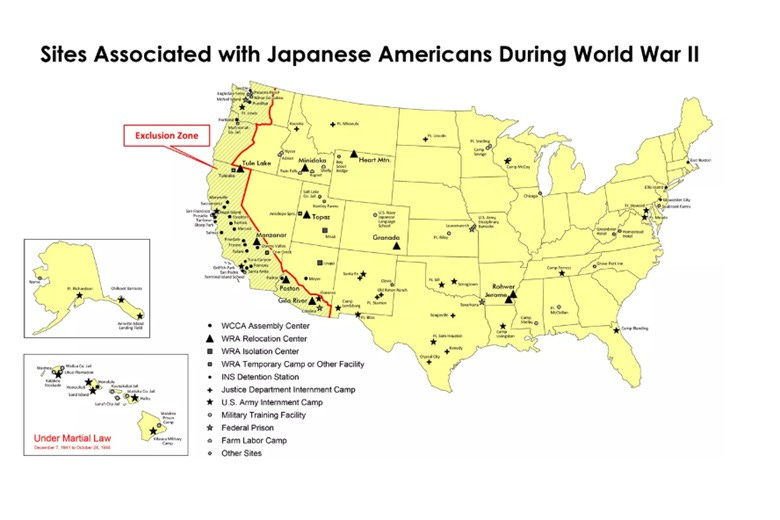

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans—two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens—were forcibly interned in ten camps across the country. Executive Order 9066 authorized the creation of “military areas” and the removal of persons of Japanese ancestry from their homes. Internment was based not on evidence of disloyalty, but on race. Idaho’s attorney general stated, “We want to keep this a white man’s country. All Japanese should be put in concentration camps for the remainder of the war.” The War Relocation Authority oversaw the incarceration in fenced camps with guard towers and barracks, where families lost property and businesses. As of 2022, approximately 1.2 million Japanese Americans live in the U.S., nearly half in California and Hawaii.

Relocation centers during World War II. NPS: Public Domain. https://www.nps.gov/articles/japanese-american-incarceration-archeology.htm

The threads of racial inequality are evident across all racial and ethnic groups in the U.S., as well as among those facing discrimination based on gender or sexual identity. Efforts to address these inequalities are now under assault, and the gains of previous decades are under threat. Racial profiling, immigration raids, and rapid deportation quotas instill fear in communities. Regarding recent cuts to National Institutes of Health research, U.S. District Judge William Young stated:

“I am hesitant to draw this conclusion—but I have an unflinching obligation to draw it—that this represents racial discrimination... I have never seen a record where racial discrimination is so palpable... You are bearing down on people of color because of their color. The Constitution will not permit this.”

When did we become a nation where people in masks, without uniforms, and in unmarked cars can take people away? It seems these tactics have long been embedded in the American psyche.

NOTES

· H. Zinn. A People’s History of the United States: 1492 – present, Revised Ed. (1995).

· N. Hannah-Jones. The 1619 Project. (2021).

· N. Blackhawk. The Rediscovery of America: Native peoples and the unmaking of U.S. history. (2023).

· M. Harris. Palo Alto: A history of California, capitalism and the world. (2023).

https://www.livescience.com/difference-between-race-ethnicity.html

https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/top-diaspora-groups-united-states-2023

https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/explore

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1866-1898/chinese-immigration

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/immigration-act

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/japanese-american-incarceration

https://www.politico.com/news/2025/06/16/judge-rebuke-trump-nih-cuts-00409095